Actually sir, I’m here at my own request… I want to see the frontier.

You want to see the frontier?

Yes sir… before it’s gone.

If you have insurance you would like us to file, please provide that information on the back of this invoice. If information is not received, financial responsibility is yours. If uninsured, contact our office for information on our discount program.

Rent $3.99

7 days free then $32.99 / month

Rent $3.99 stream with MGM+

Free with ads

Free with ads

I/III

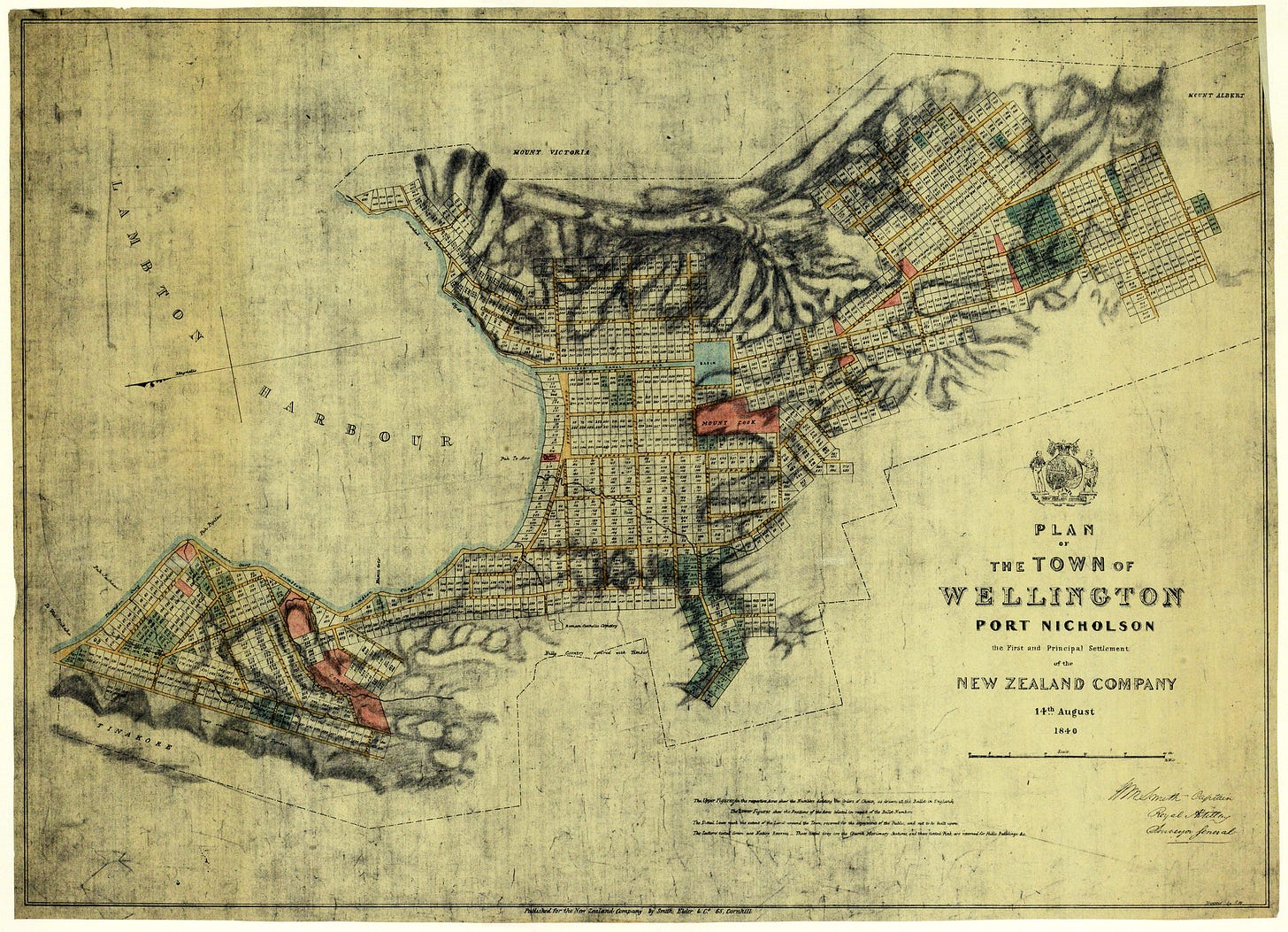

I was born on the frontier, sort of. The twentieth century watched Aotearoa New Zealand lose its outpost status in the fading eyes of a decaying global power only to regain it on the wet lips of a new one. At first, the mid-century retraction of English empire saw the centre of New Zealand politics briefly reimagine itself with a kind of limited post-colonial imagination. One lacking in the indigenous sovereignty actually required of the self-conception, but nevertheless an ambition towards international independence and Pacific responsibility that may have one day meant something.

But this imagination was nothing in the face of a much bigger dream. The last decades of that century and the first of the next are marked by our return to outpost status, under a different set of outcomes and obligations, and for a different power. By century’s end, formal treaties and defensive agreements between Aotearoa and America had faltered. Instead, we readily fell victim to a more insidious and far more effective kind of imperial embrace: America’s near-perfect brand of soft-powered cultural colonialism.

Like big sister Australia, like the countries of Western Europe, New Zealand was so filled with the cultural and physical products of the USA, borne by tides of global trade that, by the time I was born, what was American and in American interests was all too often the normative yard stick against which New Zealand measured its own cultural and political imagination.

Three things are happening. Not at once, they run on separate rails, but they are about to align in a brief and awkward orbit. Tonight is a kind of convergence, a sequencing of something inarguably real but without any significance beyond what I choose to attribute it—and I will choose to attribute a lot.

What’s to come is something like a partial contact with an object too large for description, the experience of brushing up against the edge of a thing too big for words. The feeling of being at a kind of frontier, in the psychic spaces where all sensation pushes to be felt at its utmost and where significance is a rich and undepleting resource that makes augurs of empty gestures and grows lusty symbols in the loamish possibilities of fate.

Sometimes the world is mundane and inert, and sometimes we can crib from Walter Pater and see that there ‘are oracles in every tree and mountain-top, and a significance in every accidental combination of the events of life.’1

Three things are happening. I’m dog sitting Mo, an impossibly handsome and equally anxious labradoodle at my friends’ house in suburban Austin. I’m falling fairly unwell with two minor but coincident illnesses. And I’m trying to watch Kevin Costner’s 1990 epic Western fantasy of white spiritual redemption at the edge of America, Dances with Wolves. On Tubi.

Geoff Park had the excellent idea that one might track the nineteenth-century transformation of Aotearoa into an idea of England by following volumes of Wordsworth and Coleridge, packed in the luggage of aspiring colonisers as they sailed across the ocean.2 Arriving in places like Pito-one and Whanganui, the poetic anthologies were small material missionaries, cultural missiles aimed a landscape. Ideas that could reshape place. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, a passage just like this has been repeated, faster and more frequently, just from somewhere else.

Repeated through blockbuster films and must-see television and Netflix original stand-up specials. Repeated in the YouTube video essays offering definitive rankings of Six Flags rollercoasters, seasons of Saturday Night Live, and every Rainforest Cafe in the contiguous 48. Repeated in the airport novels and beach reads, and on Oprah’s Book Club stickers. In the Dan Browns, Stephen Kings, and Danielle Steels. The Eats, the Prays and, of course, the Loves. An idea of America made the journey inside Ford Fiestas, MacBook Pros, and Doritos inexplicably called Spicy Sweet Chili in the US and Thai Sweet Chili back home. It came in the two-car garages, ryegrass lawns, and suburban-mall Starbucks that confused my nan because she’s never ordered a coffee that way before. And with blunt, angry force, it still tried making its way on the back of trade agreements, mutual defence pacts, coalitions of the willing, and trans-pacific partnerships.

These are the sticky fingers of imperialisms soft, hard, and semi-erect, sliding across the barely comprehensible width of the Pacific like slippery digits assailing our open ears with the unrelenting wet willy of peace, prosperity, and mutual growth.

Hand over hand, grasping at holds on the edge of each puckered sucker, I climbed a tentacle when I moved to the US last year. I wanted to reach back to the eldritch source to reach the stink, thinking that from the metropole I might better observe the borderlands, might see how the sausage of soft power is really made. But the great disappointment, the sad revelation that awaits all who make the trip, is that it’s all centre and all margin, all edge and all middle. I simply can’t see the core for its constant enmeshment with all that endless frontier.

Here's what I like about Tubi. They send me an email every couple of weeks, maybe once a month, with highlights of their new film and television offerings that includes a poster grid of some fresh selections.

Here’s what was in one:

Duel at Diablo (1966), The Dukes of Hazzard: The Beginning (2007), Ad Astra (2019), Platoon (1986), Soul Plane (2004), Appaloosa (2008), Thelma & Louise (1991), 3 From Hell (2019), The Unbinding (2023).

Here’s another:

Damaged (2024), Enough (2002), Independence Day (1996) Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard (2021), You Don’t Mess with the Zohan (2008), All That Jazz (1979), Repulsion (1965), The Damned (1969).

Maybe just one more:

Desperation Road (2023), Secrets and Lies (1996), Lie to Me (2009–2011), Gossip Girl (2007–2012), Gifted (2017), G.I. Jane (1997), NYPD Blue (1993–2005), Degrassi: The Next Generation (2001–2015), 187 (1997).

What is that? What does that mean? These lists send me into a Beautiful Mind tailspin, desperately trying to pin red twine between Ad Astra and Soul Plane (they both primarily take place off the ground) or Gossip Girl and G.I. Jane (Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds hold the record for highest box office weekend for a married couple, a title they took from Demi Moore and Bruce Willis in 2024. Easy).

Tubi define themselves—and in turn have been defined by agreeable media reportage—by a certain chaotic disposition towards curation and recommendation, two factors until recently seen as core values of the media streaming experience. Call it laissez faire, call it bargain bin, call it a trough full of slop, Tubi’s point of difference is that—beyond a certain point, and that point does matter—they will not do the work for you. Tubi is about finding your own way through the spaces of streaming, forming your own connections.

And what’s on there can be pretty kooky. Tubi has been described as catering to every niche, which is true in so far as a trawling net could be described as catering to every lobster. By virtue of filling their digital coffers with the cheapest and the most and the least remembered—alongside a panoply of schlocky, dirt-cheap originals—Tubi have accumulated an unwieldy catalogue of film and television as vast as it is eccentric.

People will quickly point out fan favourites like Columbo (1968–2003) and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003), but Tubi also boast excellent rarities like Prime Suspect (1991–2006) and Spencer for Hire (1985–1988), deep-genre gems and game-changers to find on a streaming platform if your proclivities lean towards horny British detectives or the other show starring Avery Brooks. Tubi have always promised this difference through depth. Unlike Netflix or Amazon Prime Video, which ask us to identify with them as a part of our daily lives and identities, Tubi is—at least in its own conception—kind of out there, on the edge.

I’m almost as horizontal as possible, flat on the bone-white couch save for a head propped forward and chin tucked down to see Tubi’s yellow on purple splash screen shine through the glass of the television. I feel unwell, pallid and foreshortened like Mantegna’s Lamentation. But instead of the Virgin, Magdalene, and John the Beloved, I have Mo the Labradoodle watching over my supine sardine of a sickly body.

In about half an hour, Lt. John J. Dunbar, Kevin Costner’s unflappable Yankee, will arrive at Fort Sedgwick—the farthest outpost of the American West—and find it abandoned. In another half hour an ambulance and fire engine will pull up outside the house to treat me for a medical emergency I’m not actually having.

In the moments before Dunbar finds the dilapidated settlement and resolves to restore it to an order becoming a Union fortification, Costner indulges in a heady montage of open plains and valleys, wide canyons, and distant mountains. Dunbar and Costner both are thinking with the frontier. Here are geographies beyond the outer edge, suffuse with romance, danger, and desire for an eye trained in taking.

These are spaces of potential, only comprehensible in their current configurations as use unrealised—electricity in a battery, opals in a mine. And the edge, the frontier boundary itself, is a meridian of progress sometimes real but always imagined, a machine that turns border into interior. After Dunbar resolves to stay on at Sedgwick, we watch him literally ploughing the land, effecting the material leg of an ideological transformation which was already complete.

Outside of this early sequence, Dances with Wolves is, in the end, a fairly traditional white-saviour narrative of guilt and redemption. Dunbar rejects the army and the codes of white settlement to live with a Sioux community, shifting his beliefs, renouncing expansion and individual property. But the arc of the movie doesn’t really matter, it’s little more than a reactionary liberal fantasy of the dying twentieth century—moral expiation for all that’s represented in the unyielding metaphor of Fort Sedgwick, standing in for white America better than Dunbar or Costner ever could.

For all the time I spend thinking about the intangible connections between America and Aotearoa, it is worth remembering the ways that we are linked, quite literally, physically, by impossibly long cables of plastic and copper and steel and fibre optic glass. For almost two decades, from 2000–2018, New Zealand was joined to the internet by a single tether: the Southern Cross Cable. The temporal length of this connection is squarely attested by the state of its website, but its physical span is something to behold. The Southern Cross Cable is an infrastructural leviathan that loops an awkward figure eight connecting Australia and Aotearoa with the US through a pinch in Hawaii and termini in California and Oregon.

It’s a small miracle that Aotearoa navigated the 2000s and 2010s relying on a single internet connection, a sole link to the most important technology of the century, one pipeline—with landing stations in Takapuna and Whenuapai—allowing us to work, communicate, organise, and entertain.

In recent years a number of new submarine pipelines, commercial competitors to the Southern Cross Cable, have bolstered the physical link from New Zealand to the US, to Australia, to the island nations of the Pacific Ocean, and to itself. More are scheduled to come online next year.

Looking at a map of this burgeoning network, it’s hard to avoid comparison with textbook graphics of England’s physical transformation by rail in the nineteenth century. First a few snaking lines in the coal fields, then links between London and the industrial cities of the north, and on until a matrix in wrought iron and steel, a winding lattice of industry, covered the face of the British Isles like Spanish moss.

The comparison is aesthetic, and to a degree coincidental, but it’s also kind of essential. In The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Space and Time in the Nineteenth Century (1977), Wolfgang Schivelbusch convincingly argued for an understanding of railroads as a ‘machine ensemble’—a kind of total mechanical organ including tracks, engines, and stations—that did more than just quicken transit and make travel scheduled and uniform.3

Schivelbusch, writing in the 1970s as commercial jet travel was effecting a similar transition, saw the railway as a technology of speed and distance that fundamentally reoriented the experience of space-time. Shortening the time it took to travel from one city to another, railways brought urban centres closer in perception. And in their newfound proximity, connected by newly nationalised networks of trade, cities became more alike to one another.

At the same time, the fields and villages of rural life were now something seen whistling past a window, never stopped for, no matter how much an individual passenger might benefit from the detour. Cities grew closer, and larger, and the country faded from view. As the network expanded—reaching ever further outward—the pattern repeated itself, the mono-city repeated itself, over and over. Wild edge became frontier, frontier became border, border became margin, and margin became middle.

If this transformation could be achieved with hard metals and a steam engine, what might be possible with links laid of polyethylene and optic fibre? Isolated nations now physically touch, they have since the first transatlantic telegraph cable was laid in the 1850s—the beginning of a network of networks beneath the ocean. Those early cables were superseded by telephone lines, which have been superseded by internet lines that now compete with each other for delivering ever higher speeds of gluttonous connectivity.

In the late 1940s, Martin Heidegger began to warn—only after the defeat of his beloved Nazis—that while technology might make the world more proximate, it neither generated nearness nor erased farness. Instead, technology was to give us a kind of total distancelessness, a spatiality wherein everything is available but only to be used in the further expansion of technology itself.4

The continents are pulling at each other, bringing each other closer, remaking each other in their own increasingly monocultural likenesses, and erasing the spaces between faster than the railroads ever could. Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa is receding from view and in its stead there is simply Takapuna / California. And these cables don’t traffic in coal or cattle, they run in the freight of the internet: content. The network of submarine cables sits silent at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, in that total and dread darkness, hulking, unmoving, bringing Tubi to you and me.

*

Walter Pater, The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry: The 1893 Text, ed. Donald L Hill

(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1980 [1893]), 35.

Geoff Park, Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape & Whenua (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2006), 118-119.

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Space and Time in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Urizen Books, 1979 [1977]), 27.

Martin Heidegger, Insight Into That Which Is in Bremen and Freiburg Lectures trans. Andrew J. Mitchell (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012 [1949;1957]), 23; 42.